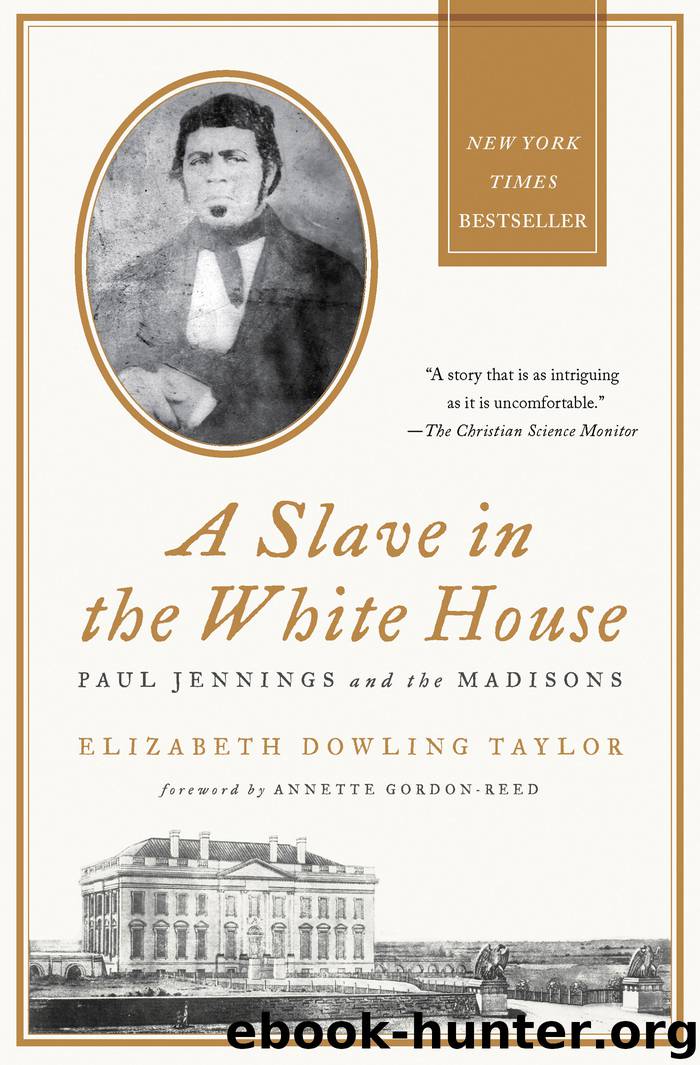

A Slave in the White House by Elizabeth Dowling Taylor

Author:Elizabeth Dowling Taylor

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2019-04-17T16:00:00+00:00

BY THE TIME JAMES AND DOLLEY RELOCATED from Philadelphia to Virginia and had four rooms added to his father’s house, she was deeply in love with her husband. Theirs was to be a supremely successful union on both a personal and public level, prevailing for forty-two years. When they moved to Montpelier in 1797, Dolley had Payne, now five, in tow of course. Dolley’s sister Anna Payne, or “sister-daughter” as she called her, her junior by eleven years, completed the family unit. The foursome lived with James Sr. and Nelly (only their youngest child, Frances, was still at home), who continued to occupy the original part of the house, while the new rooms, two over two, were added to the formerly exterior north wall. Though there was still finishing work to do, the “vortex of housebuilding” was largely completed when Madison informed his friend and political associate James Monroe on 30 January 1799, “We have now been near six weeks settled in our new domicil.” 15

Thus Paul Jennings was born as the younger Madisons set up housekeeping in their part of the mansion, now a kind of duplex or row house for the two generations. The domestic slaves lived in cabins in the yard immediately to the south of the mansion. Baby Paul and his mother might have lived in a duplex, too—at least this was the form that the south yard slave dwellings took later—in a household that included additional kin or connections. Paul Jennings’s birth year of 1799 started with snow on 3 January, the fifth snow of the season already, but by the first day of April the apricot blossoms were opening and the seasonal shift in work on the plantation was under way. 16

Madison’s return to Virginia in the late 1790s signaled a true hands-on management of Montpelier’s five thousand acres and five-score people. Though tobacco continued to be cultivated, wheat was now the major crop. Raising cash crops (a misnomer for some harvests) was just one of many occupations and activities that planters and their enslaved people tended to. Even given the livestock, gardens, orchards, and mills, farms like Montpelier never reached full self-sufficiency. Some commodities, such as salted fish, coffee, salt, and sugar, were purchased from merchants in Fredericksburg or other cities. Locally, county farmers bought and bartered produce and game among themselves. Francis Taylor, a nephew of Madison’s grandmother, left a diary with scores of such transactions recorded. For 1799, he entered on 1 April: “intended to send soon to Madisons mill for cyder &c.” On 25 September of that year he described the errands of two Montpelier slaves, Tyre and Sam. He noted that James Madison Jr. “sent Tyre to whom I delivered 3 Gammons, 2 Shoulders, & 1 Midling 86 lb Bacon—Tyre carried a Basket Peaches home . . . Col J Madison sen’r sent some pairs by Sam & got two baskets Peaches.” Taylor caught up with the younger Madison for payment some days after; on the evening of 6 October, he received “a Doubloon pound sterling 4.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| U.K. Prime Ministers | U.S. Presidents |

Waking Up in Heaven: A True Story of Brokenness, Heaven, and Life Again by McVea Crystal & Tresniowski Alex(37810)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23086)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

Hans Sturm: A Soldier's Odyssey on the Eastern Front by Gordon Williamson(18591)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13336)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8396)

Educated by Tara Westover(8054)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7486)

Permanent Record by Edward Snowden(5847)

The Last Black Unicorn by Tiffany Haddish(5635)

The Rise and Fall of Senator Joe McCarthy by James Cross Giblin(5280)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5153)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5095)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4817)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4356)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4110)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3965)